This bugzilla comment came across my desk this morning:

If there are any developers out there interested in implementing this functionality (to be contributed back to Mozilla, if it will be accepted) under contract, please contact me off-bug, as my company is interested in sponsoring this work.

The comment applies to a mozilla enhancement request for SRV record support. SRV records are part of the DNS system, and would allow one level of server load balancing to be performed by client machines on the internet of today. Unfortunately, HTTP is a protocol that has not wholeheartedly embraced the approach as yet. What I think is interesting, however, is that there are customers who find bugs and want to throw money at them.

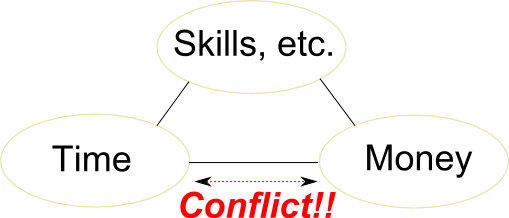

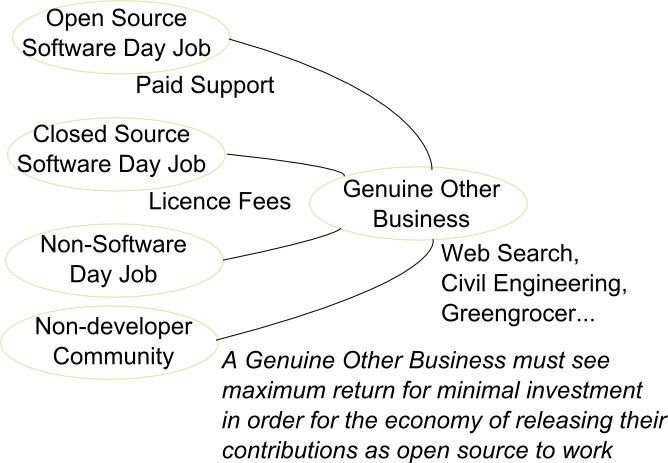

The extent to which this is true will be a major factor in the success of Efficient Software. This particular individual would like to develop a 1:1 releationship with a developer who can do the work and submit it back to the project codebase. I wonder how open they would be to sharing the burden and rewards.

This is the kind of bug that seems likely to attract most intrest for the Efficient Software initiative. It has gone a long time without a resolution. There is a subset of the community with strong views about whether or not it should be fixed. There seems to be some general consensus that it should be fixed, but for the project team for whatever reason it is currently not a priority.

It is unclear whether putting money into the equation would make this bug a priority for the core team, or whether they would prefer to stick to more release-critical objectives. There may be a class of developer who is more occasional that could take on the unit of work and may have an improved incentive if money were supplied. That is how I see the initiative making its initial impact: By working at the periphery of projects. I don't see the project being a good selector of which bugs should recieve funds because, after all, if the cashed up core developers thought it was release critical they would already be working on it. No, it is the user base who should supply the funds and determine which bugs they should be directed to.

There are important issues of trust in any financial transaction. I think that an efficient approach can adress these issues. The individual who commented on the SRV record bug is willing to contract someone to do the work, but whom? How do they know whether the contractor can be trusted or not? The investor needs confidence that their funds will not be exhausted if they are supplied towards work that is not completed by the original contractor. Efficient software does this by not paying out the responsible party (the developer or the project) until the bug is actually resolved. Likewise, the contractor must know their money is secure. Efficient Software achieves this by requiring investment is supplied up-front into effectively an escrow account while the work is done.

The biggest risk for an investor is that they will put their money towards a bug that is never resolved, despite the incentive they provide. A project may fork if funds are left sitting in the account. The investor's priorities may change. They may want that money put to a more productive use. I don't know of any way to mitigate that risk except to supply more and more incentive, or to first find a likely candidate to perform the implementation before actually putting funds into escrow. Perhaps the solution is to allow investors to withdraw funds assigned to a bug up until the bug is commenced. Once work is started, the money cannot be withdrawn. If the developer fails to deliver a resolution they may return the bug to an uncommenced state and investors can again withdraw funds to put to a more productive use.

The fact that the efficient software approach is an emergent phenomenon gives me increased confidence that it can be developed into workable process. In time, it may even become an important process to the open source software development world. Do you have comments or suggestions regarding an efficient approach to software? Blog, or join us on our mailing list.

Benjamin