We had a good preliminary scoping discussion today at HUMBUG. I caught the end of Pia Waugh's talk, and the linux.conf.au 2006 debreif lead by Clinton Roy. After dinner a few of us clustered around a chalk board at the front of the lecture theatre. A good canvassing of some of the direction issues was had, despite most of it being carried out before Anthony Towns returned from a separate dinner trip.

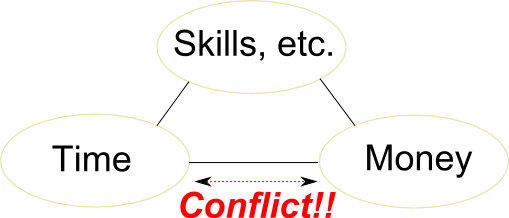

I was on the chalkboard, and wrote up the Efficent Software Initiative problem statement as follows (excuse my basic inkscape reproduction):

Libre software is often written gratis, however those who write the software still need to live. They need to feed their families. In short, they need a day job. A lucky few are employed to write open source software for specific companies that use it. Many others are weekend soliders.

We are at a stage in the development of the software industry as a whole where it is usually necessary to be a full time software developer in order to be a particularly useful software developer. It takes a number of years of study and practical application to write good software, and we want our free software to be good. For those not employed to work on open source, their day job will likely include closed source software. Now, let's assume we "win". There isn't any appreciable amount of closed software development going on anymore. Do these guys lose their day jobs, or can they be employed to work on open source software in a new and different way? It is the function of the Efficient Software Initiative to build a base of discussion and experimentation to answer that question. We want to give as many people as possible the chance to work full time on free software, which means giving them an income.

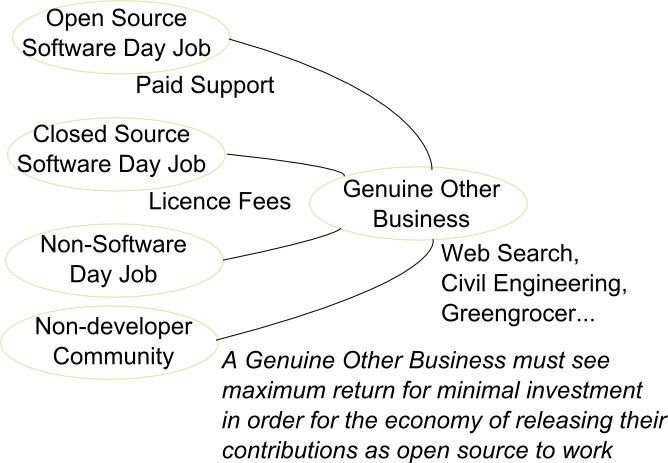

The initial diagram became a little more complicated as we tried to model the software industry that supports open source developers today. We started by drawing links to that all-important money bubble. The goal was to describe where the money is coming from, including where a business that employs open source software develpers ultimately gets its money from. A simplified version of the diagram follows:

If free software takes over we lose the ability to charge licence fees to support the developer's day job. I see the support-based business model for software development as weak, also. It may have conflicting goals to that of the production of good quality software with a balanced feature set. Real strength in an open source business model comes from being useful to other industries. That does not necessarily mean outside the world of computers. Google or Yahoo have established business models in the internet search industry, and serving their interests is a way of rooting the money supply available to open source without depending on closed software in the value chain. Other industries and established business models abound, including everything from avionics to resturants. To be productive, an open source industry has to appeal fairly directly to this wide audience. These industries can and should be engaged incrementally and won over with sound business logic.

So if we trace our connections back to the developer, we see two main paths still open for the raising of funds. We could try and get them employed directly by businesses that need software and want their particular interests represented in the development of a project going forwards. Alternatively, we could try and raise money over a wider base from the whole user community. This is a community of individuals and of companies who have an interest and an investment in your project's ongoing success. Your project represents a point at which their interests all overlap. The main things that matter on an encomic level in maintaining the community and successfully drawing contributions from the community are to match your project goals with the community interests and to ensure that individual contributions are returned in spades as a collectively built product.

This is an interesting and important facet to the bean counting motivation for open source in business. Businesses like to deal with the existing software industry. They pay a small fee, and in return they get to make use of the produce from hoards of programmers over several years (if not several decades). Open source makes it possible to do the same thing for business. Even though they contribute only a small amount individually, they each recieve the benefit of the total common contribution. They often don't need to work on a bug that affects them to see it fixed. The effort is often expended by someone else who felt the pain more stronly or immediately. Licences such as the GPL also provide some level of certainty to contributors that what they have collaboratively built won't be taken by any single contributor and turned back into a product that does not benefit them.

The difference between open and closed source approaches to this multiplicative return is that open source is more efficient. It stands to reason that when it is possible to fork a product, there is a lower cost of entry to the business than if you had to rewrite from scratch. For an example, just consider the person-years of effort that have been extended on the GNU Classpath, despite Sun having a perfectly good implementation in their back pocket the whole time. If the barrier to entry is lowered, competition or the potential for it increases. This should lead to a more productive and lower cost industry. The current industry forms monopolies wherever there is a closed file format or undocumented API. An industry remade as open source would see none of that, and the customers should benefit.

Benjamin